Older workers have expertise based on years of experience and make an important contribution to the economy. Photo: James Alcock

I suspect if you were to ask many of those in their late 40s and older if ageism could hold Australia back, their answer would be “yes”. That disappointing view would invariably be based on their personal experiences in the workforce.

Ageism will hold us back because, with an ageing population, we need to increase participation by older workers in the workforce.The evidence over recent decades indicates older people are underemployed for longer periods than younger workers. Australian Bureau of Statistics figures show more than 35 per cent of jobseekers aged 55 and over stopped looking for work because they believed potential employers thought they were too old.

As a society, we are discarding valuable older workers far too early.

These older people excluded from the workforce account for more than half the total number of jobseekers who gave up looking for work.

Older workers face ageist stereotypes and biases, especially in the workplace and in recruitment. These negative attitudes label them as too costly, too inflexible and too difficult to train. As a society, we are discarding valuable older workers far too early.

To safeguard our way of life, we must maintain our incomes and keep people in jobs. In short, we need to keep the economy growing. One of the key drivers of long-term growth is widely recognised as having more people in the workforce.

Unfortunately, if we do not adjust our approach, the long-term outlook for Australia is lower economic growth. Why? Because our population and our economy are changing and that will impact heavily on our workforce participation.

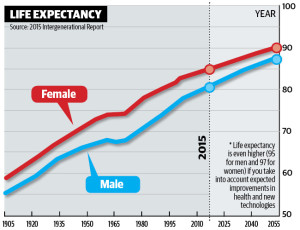

The government will soon launch the 2015 intergenerational report. The report is the most comprehensive examination of demography and current policy. It evaluates how these changes will affect the economy and government finances over the next 40 years.

It will show there will be fewer people of traditional working age as a proportion of the population in the years to come. Over the next decade, the working population is expected to increase by 12 per cent, while the population over 65 is expected to increase by 36 per cent. That is, the number of people aged over 65 will grow three times faster than the traditional working-age population.

The number of people in the traditional workforce supporting those who have left the workforce will nearly halve over the next 40 years.

On the one hand, this a problem, because as the population ages and more people leave the workforce, tax revenues will struggle to fund the same level of government services we enjoy today. On the other hand, this is an opportunity to encourage greater workforce participation, especially among underappreciated and underutilised older people.

We must not fall into the trap of viewing an ageing population as a burden. Older people will be critical to maintaining the economic growth that has underpinned the advances in our standards of living and quality of life.

According to the age discrimination commissioner: “As a society, we have been slow to recognise that millions of older Australians are locked out of the workforce by age discrimination. We are only now starting to understand what a terrible waste of human capital this situation represents; a loss to the national economy and to businesses large and small, and a loss to the individual who is pushed out of the workforce prematurely.”

Deloitte Access Economics estimates a 3 per cent increase in participation by the over 55s would generate a $33 billion annual boost to the national economy. A 5 per cent increase in participation, would see a $48 billion boost to the economy.

If Australia’s workforce participation rate for those aged over 65 increased to that of New Zealand over the next 10 years, this would result in a boost to Australia’s real gross domestic product of about $40 billion in 2024-25.

Older workers contribute knowledge and skills based on years of experience and expertise. We need older people working and contributing to our economic growth.

Also, people who work longer accrue more superannuation savings and are less reliant on the pension during retirement.

There is a strong correlation between workforce participation and health status. Continuing to work protects against physical ill-health and poor mental health. Data shows people staying in the workforce past retirement age tend to have better health compared with those not working.

Older workers also report the need for flexibility in their working hours or part-time arrangements so they can fit in caring responsibilities or manage sickness or disability.

The decline in participation rates of older workers only aggravates the problem of age dependency and rising social expenditures. Ignoring a pool of productive workers in the face of a falling participation rate will affect our economic growth.

If these trends continue, we as a society will be contributing to a decline in our standard of living. So let’s reverse the traditional attitudes, embrace a longer life and look for ways to redesign our lives so we can enjoy prosperity along the way.

Joe Hockey is the federal Treasurer.

The new year has kicked off on a sour note for the economy with the unemployment rate jumping to 6.4%, the highest in 12 years.

For the past decade, Australia got used to having the unemployment rate around 5%, plus or minus a percentage point, depending on the nature of the positive and negative shocks that hit the economy and the policy response to those shocks.

The gurus at the Reserve Bank of Australia and treasury expect the unemployment rate to rise in the near terms and stay above 6% for several more years, even though interest rates are at record lows and the Australian dollar has fallen by 30% over the past three years.

The causes of the recent spike in the unemployment rate must be understood if it is to ever fall back to 5% or less.

In very broad terms, there are two important determinants of the unemployment rate: the pace of economic growth and wages. There are other drivers including education, skills, demographics, social welfare, but these are more medium-term issues that have probably not been significant factors behind the recent bad news on unemployment.

It is difficult to make a case that it is wages or labour market inflexibility that is behind the recent jump in unemployment. Wages growth has slowed markedly, to levels not seen for at least 40 years. The labour market, through these miserably low levels of wages growth, is adjusting to changing circumstances. In time, these flat or falling real wages will mean demand for labour will be higher than if wages growth was stronger. What is more, unit labour costs are actually falling, which is evidence that employers are not finding wages costs to be a major factor when it comes to hiring new staff.

The problem for unemployment is quite obviously the pace of economic growth. There is simply not enough economic activity in the economy to stop a significant part of the increase in population growth going straight into unemployment rather than being taken up in employment.

Given the mix of population growth, productivity and the composition of the Australian economy, annual real GDP growth needs to be maintained at around 3.25% for there to be enough jobs created to keep the unemployment rate steady. This is what many refer to as the long-run trend growth rate for Australia.

When the December quarter 2014 national accounts are released in early March, they will confirm that real GDP growth has been below 3.25% for nine consecutive quarters (over two years) and in that time has averaged just 2.4%. In other words, for those two years, the economy has fallen around 0.75% short a year of the growth rate needed to keep the unemployment rate steady, let alone push it lower. It is no surprise given this weak economic performance that the unemployment rate has risen by more than 1 percentage point.

The solution, it should be obvious, is to have in place policies that will fire up the economy so that GDP growth can be at least 3.5% for a couple of years so that the unemployment rate can fall back.

The RBA is doing its bit, cutting interest rates to record lows, but is mindful of having monetary policy inflating unwelcome house price gains.

With the budget three months away and the labour market weakness now entrenched, the case for job-creating fiscal stimulus should be considered. The treasurer, Joe Hockey, is speaking of bringing forward expenditure on infrastructure projects, which history shows is cumbersome and slow to deliver the economic growth needed to make a meaning impact on employment. There is also discussion about tax cuts for small business which, again, are long-run issues and unlikely to be implemented before July, a point when the unemployment rate is likely to be 6.75%.

Of course, if the Abbott government were to consider any other stimulus measures, it would be breaking more promises as, by definition, stimulus measures mean a larger budget deficit and higher levels of government debt. The Coalition was swept to power in 2013 on a promise to return the budget to surplus and reduce government debt.

The issue for the 800,000 people currently unemployed should be more about the policy response and not politics. If politics win out and the policy settings err on the side of moving the budget towards surplus and cutting government debt, it is likely that by the time of the next election in the second half of next year, there will be more than 900,000 unemployed. This is not the sort of legacy that in the heat of an election campaign would be easy to defend.

Stephen Koukoulas is a research fellow at Per Capita, a progressive thinktank.

Source: The Guardian